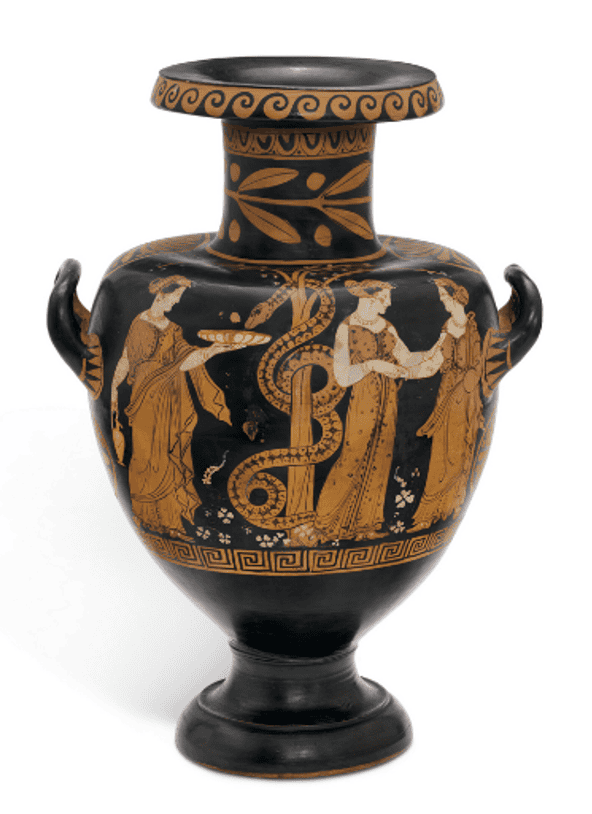

Snake Medicine

Hesperides feeding the serpent Ladon, the sleepless guardian of the golden apple tree

mid–4th century BCE (ca. 350–330 BCE)

Campanian hydria (Zurich, Roš Collection)

Snakes, Venom, and Medicine in Greek Myth & Ritual

A serpent coiled around a vessel, its head poised at the rim, is among the most enduring symbols of medicine and pharmacy. Today it is commonly known as the Bowl of Hygieia. Modern viewers are often told the snake is “drinking,” but this reading is both late and misleading. Across Greek ritual, myth, and iconography, the vessel is better understood as a site of venom collection, pharmakon exchange, and ritual preparation. What appears as “feeding” is more accurately milking—the harvesting or controlled transfer of venom for medicinal and initiatory use.

This image circulated in the Mediterranean world from at least the second millennium BCE, during the Bronze Age. Over time, its meanings accumulated rather than disappeared, preserving a deep association between serpents, medicine, death-return rites, and controlled danger.

Modern pharmacy logo derived from the ancient “Bowl of Hygieia” motif.

Source: Wikipedia.

Bronze Age Origins: Ritual, Death, and Medicine

In Minoan and Mycenaean Greece, as well as in Cyprus and the Levant, snakes and vessels appear together in both religious and funerary contexts. These were not decorative pairings. They belonged to initiation environments—spaces concerned with death, return, and transformation. By the eighth and seventh centuries BCE, Greek examples of the motif appear almost exclusively in funerary settings.

Jugs and cups from this period show serpents coiling toward vessels. Rather than passive consumption, these scenes align more coherently with ritual extraction or offering of venom, a pharmakon employed in healing or initiatory rites for the dead and the living alike. The vessel functions as a controlled interface between human handlers and a powerful, dangerous substance.

Heroes, Snakes, and the Underworld

By the fifth century BCE, Spartan artists began integrating the serpent-and-cup motif directly into scenes involving human figures. Spartan culture placed extraordinary emphasis on heroes—mortals elevated after death through endurance, ordeal, and proximity to underworld forces.

Laconian stone hero relief, 3rd century BCE. Sparta Museum 3360 (photo: Gina Salapata).

A long series of Spartan reliefs shows seated male figures extending cups toward snakes. Originally interpreted as “offering a drink,” these images are better understood as venom use in initiatory rituals. The hero, having drank the venom pharmakon from the cup, now dwells among the dead yet active among the living, travels between worlds through the pharmakon. The snake—an underground, chthonic being—is not evil but essential: it offers through venom dosing controlled access to revelatory states, through a guided "death" and return "resurrection", symbolically represented as a journey to the underworld and back.

Here, “underworld” does not mean punishment. It refers to initiatory descent, the hero’s mental journey through danger, dissolution, and reconstitution. Resulting in purification of the mind, the "forming" or "molding" of the person, by harmonizing their mental kosmos or internal structure or ordering of the mind, what Greeks called the psuche (psyche or soul). Venom pharmaka — thanasimon (death-inducing storm) balanced by galēnē (calm, antidote) — belong squarely to this domain, and was the technology of descent and return, to provide initiatory fire to reforge the initiate Hero.

As this iconography spread across the Greek world, especially into southern Italy via Spartan colonies such as Taras, it retained its initiatory force while expanding its narrative range. Mythic women now appear alongside serpents and vessels, engaging heroes at pivotal moments of transformation.

Heracles and the Garden of the Hesperides

The Hesperides tending to Ladon.

Campanian hydria, ca. 350-40 BCE. Zurich, Roš Collection.

https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-6492119

Southern Italian vase painters of the fourth century BCE frequently depict the Garden of the Hesperides, a divine enclosure of perpetual vitality reminiscent of later Edenic imagery. At its center grows a tree bearing golden apples—objects of immortality—guarded by the sleepless serpent-dragon Ladon.

The Hesperides are regularly shown holding a bowl to the coiled dragon. Modern interpretations often claim they are drugging or distracting Ladon so Heracles can steal the apples during his eleventh labor. This explanation collapses under scrutiny. The same scene appears even when Heracles is absent, indicating that the action represents routine ritual practice, not deception.

The Hesperides are tending the guardian, collecting it's venom. They are milking or harvesting the serpent’s pharmakon, maintaining the equilibrium of the sacred garden. The venom is the fruit of the serpent beast, symbolized by the more familiar apple fruits. As with priestesses who tended temple snakes elsewhere in Greece, their role is custodial and technical. The serpent is sacred because its venom is powerful—useful in healing, gnosis, and initiation.

In this context, the bowl is not a bribe but a collection tool. The dragon (drakōn / ophis) is a guardian of relics: knowledge, secrets. Such things as fire induced rebirth, life-renewal, enlightenment, immortality, reordering, restructuring, formation / molding of the soul.

The pharmakon extracted from Ladon belongs to the same idea as "knowledge taken from the tree” — not metaphorical belief, not technical knowledge, but gnostic transformative experience.

Jason and Medea: Pharmakon as Agency

Medea riding the dragon chariot

serpents give her mobility

Jason taking the Golden Fleece with Medea’s help. Roman wall painting, 2nd century CE. Trier.

a serpent provides access to the Golden Fleece

A parallel but contrasting vision appears in the myth of Jason and Medea. In Colchis, the Golden Fleece is guarded by another sleepless serpent in the grove of Ares. Medea—priestess, pharmakeia-bearer, and descendant of Circe—intervenes not through brute force but through pharmakon mastery.

Southern Italian vase painters emphasize Medea’s role by showing her holding a bowl out to the dragon. This shows a targeted pharmakon application, manipulating venom, antidote, and soporific compounds to induce the required state in Jason. Only through this intervention can Jason succeed to experience the golden fleece, a product of his venom induced initiation.

Where the Hesperides maintain order through routine tending, Medea alters the protocol. She introduces additional substances to override the dragon’s vigilance, temper and control the affects of the venoms. This deviation marks her transformation — from dutiful priestess to autonomous agent and authoritative expert practitioner. Later moralizing traditions cast her as dangerous, but this judgment reflects anxiety about female control over pharmakon technology, not its inherent nature.

Medea's legacy as a healer and pharmakeia figure was preserved in Colchis (1300-1200BCE) and later among the Medes (900-700BCE), who associated her name with medicinal power and built temples to her celebrating her healing and antivenom powers. Asclepian, Sibylline, Oracular, and Pythian traditions clearly derive from this lineage.

There's evidence that the Abrahamic prophetes, like John the Baptist, and Jesus the christed one, derive their Magian-funded arts from the same Hellenic snake traditions:

- Revelation 3:18: "christ the eyes so that the blind may see the invisible";

- Acts 28:3-6 "Paul is immune to snake venom"

- Mark 14:33–35: A private, pre-arrest episode. Jesus alone, with selected witnesses, enters an ecstatic destabilizing death-proximate state.

- Mark 14:48 - Mark 16:7: the arrest / crucifixion / cave scenes shows evidence of Dipsas (thirst viper) poisoning symptoms of extreme thirst, with a helpful neaniskos with a likely-medicated sindon bandage, and a vinegar antidote applied, early coma, and massive amount of water imbibed to quench that venom induced thirst.

- Mark 16:17-18: “...they will pick up snakes with their hands; and when they drink deadly poison, it will not hurt them at all...”. A post-resurrection address to followers. It describes what his followers can now endure or survive, the thanasimon drug. These are words spoken after the arrest / crucifixion / cave scenes that authorize or task followers to act going forward.

There's a reason so many visions, messages, and revelations were happening, and that's pharmakon with guidance. There's a reason that most biblical "supernatural" experiences were proceeded by some mention of incense, thanasimon, pharmakon, muron, or other substances (nard, myrrh, kannabis, asterion, etc.). It's simply continuity from the previous 1000 years of healing, myth, pharmakon, snakes, venoms, underworld mythography, and Asclepian and Hippocratic healing snake traditions. All derived from Medea.

Pharmakon: To Heal and To Harm

The substances exchanged between snake and vessel are deliberately ambiguous. They can nourish or subdue, heal or dissolve. This duality is not accidental—it defines pharmakon itself. In Greek thought, a pharmakon is a tool, not a moral category. Its effects depend on dose, preparation, and intention.

This ambiguity appears vividly in Homer’s Odyssey. Circe prepares a drugged potage that renders Odysseus’ companions docile, obedient, and easily managed—described metaphorically as “swine,” not as literal animals but as humans reduced to tame livestock-like states through pharmakon. Later, she applies a different preparation, restoring them through an anointed salve that reverses the condition and renews their vitality.

The same substance class both harms and heals. The difference lies in knowledge and control.

Hygieia and the Medical Legacy

Asclepius and Hygieia with a serpent and bowl. Late 5th century BCE. Istanbul Archaeological Museum.

It is within this framework that Hygieia, daughter of Asclepius and personification of health, inherits the serpent-and-bowl motif. In reliefs, she is shown holding a vessel to a snake—not as a passive feeder, but as a practitioner engaged in medicinal collection. The snake’s venom, lethal in excess yet therapeutic in controlled measure, embodies the same pharmakon logic seen throughout myth.

In later abstraction, the contrast between the living serpent and the crafted vessel comes to symbolize the balance between natural healing potency and human technique. Healing does not arise from eliminating danger, but from mastering it.

Though modern pharmacy logos have stripped the image of its initiatory depth, the symbol still carries its ancient warning: medicine is never neutral. It demands precision, responsibility, and respect for forces that can both destroy and restore.

What the Symbol Still Teaches

Modern pharmacy has inherited the serpent image while largely forgetting its depth. Yet the lesson remains intact: venom was at the center of very ancient practices, for a long time.

Long considered powerful technology, highly technical, later mythologized, later demonized, and eventually forgotten.

The Bowl of Hygieia reminds us that medicine arises not from purity, but from precision — from knowing how much, when, and why. Venom becomes remedy. Risk becomes cure.

Read the instructions carefully. The ancients certainly did.